This post is for the Japanese Cinema Blogathon. It was started to help assist in the earthquake & tsunami relief. If you like my post/hate my post/are bored to tears by my post, or just enjoy the damn pictures, PLEASE help. Living, as I do, in an earthquake-prone locale (Southern California), earthquakes are quite frightening, and I would like to do my part. Since I am broke as hell, all I can realistically do is what I do best: write. And so I will write for Japan, and hope that someone makes a donation off of what I’ve written or just makes a donation, period. Japan has given us some of the most incredible cinema in the entire world and will continue to do so. Let’s help out a little in appreciation, shall we?

The standard assumption about modern Japanese culture is that because it contains elements familiar in the west, perhaps even born in the west, it has become, in effect, entirely Westernized. Looking closer at Japanese culture, however, we can see that this assumption is about as ridiculous as saying that the United States has become more Chinese because a good many people prefer that cuisine. It is only an example of the kind of binary thinking that revisionist histories and neo-colonial thinking have created within the world that would necessitate this kind of compartmentalization.

Within this essay, I will be looking at an example of Japanese cinema that expresses not only the Japanese-ness noted previously, but also certain aspects of cultural hybridity and significance within Japanese culture. In order to explicate my argument, I will be using a variety of texts varying from discussions of cultural hybridity and Japanese history to Hamid Naficy’s work on accented cinema. What I hope to show in this work is the remarkable ability of one culture (Japan) to reappropriate and “poach” different themes and iconographies from another culture (United States) and feed them through their own, culturally specific machinations in order to create something wholly new and different.

The film I have chosen, Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961) illustrates the ways in which cultural identity is asserted through the conscious blurring of boundaries and intentionally fluid interpretations of genre. By re-placing the American Western within historically important samurai contexts, Japanese cinema can be seen to be making its own cinematic space.

This claiming of cinematic environment and demand for a location of cultural expression places modern Japanese cinema squarely within the definitions of Third Cinema. As defined, Third Cinema is “an alternative cinema…a cinema of decolonization and for liberation.”[1] By retaining individual signifiers and insisting upon their own generic interpretations, these films reject cultural depreciation and celebrate ethnic identity, and expound the tenets of the Third Cinema in a very localized fashion.

In order to truly understand Japanese cinema, it is crucial to know the history of the country itself. As Teshome Gabriel writes,

Lacking this historical perspective, the film critic or theorist can only reflect on the ways in which this cinema undermines and innovates traditional practices of representation, but he/she will lose sight of the context in which the cinema operates. An equally significant component of the critical perspective that must be adopted is the recognition of the TEXT that pre-exists each new text and that binds the filmmaker to a set of values, mores, traditions and behaviors- in a word, “culture”—which is at all moments the obligatory point of departure.[2]

Thus, in order to not fall into the “trap of auteurist fallacies and ‘aesthetic’ evaluative stances,”[3] I shall give a brief historical and cultural outline of Japan. Although by no means exhaustive, I will cover the primary events that many historians feel to be the most essential and transformative, as well as those occurrences that have singular importance to my argument.

Although there was clearly a great deal that went before, the Heian period, which lasted from 794 a.d. to about 1185 a.d., is where we will begin. During this era, there was a “flowering of classical Japanese culture in new capital of Heian-kyo (Kyoto). Court aristocracy, especially women, produced a great body of literature–poetry, diaries, the novel The Tale of Genji–and made refined aesthetic sensibility their society’s hallmark.”[4]

image from the illustrated scroll, "The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari)" - a narrative novel authored by Lady Murasaki; painted by Takayoshi in the 12th century

The cultural product that resulted from this period was significant and vital, being reproduced continually even today, within Japanese painting, cinema and television. However, although the creative vitality still existed, the relative peace was not to remain, as the Kamakura Period (1185-1333) ushered in the beginning of military rule. The significance of this was vast, as it replaced noble rulers with the samurai (warrior). Although there is recognition of artistic development during this time, the primary feature for over a century is civil war, and until approximately 1600, Japan is immersed in Sengoku Jidai (Era of the Country at War). There is no unified Japan, only a series of warlords fighting with each other. Intriguingly, this is also the period during which the Portuguese enter the Japanese islands and introduce firearms and attempt missionary work to convert the Japanese to Christianity. The Portuguese fail in their religious mission, however, and are punished severely for attempting to dilute the national culture.

In 1568, a man named Oda Nobunaga starts the process of reunifying Japan. Followed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the foundation of modern Japan is laid. However, although these men laid down the base, it was up to another man to change the course of Japanese history forever. After he brutally beat Hideyoshi (and a few years later forced Hideyoshi’s legitimate heir to commit seppuku, ritual suicide), a man named Tokugawa Ieyasu became the Shogun, and ruled with a strict, isolationist sensibility. He cut off exchange with all countries except China and the Netherlands, expelled Portuguese missionaries and essentially shut the doors of the country for 200 years. Michael Cooper, the former editor of Monumenta Nipponica, an interdisciplinary journal on Japanese culture and society, states quite simply that, “Tokugawa wanted to clear the board of all these foreign influences which were just muddying the waters, making life more complicated.”[5] And clear the board he did. Not only was trade extremely limited, but also foreign books were outlawed, travel abroad was forbidden. For 200 years Japan was kept away from the rest of the world, and the rest of the world was kept out of Japan.

During this period, however, the Japanese had ample time to refine and hone its multitude of cultural assets, without any infiltration or any disturbance from anyone. Literature, ritual customs, art, and theater all prospered in this period. However, this could only last for so long. Finally, around 1867, the Tokogawa shogunate was ended and this started the Meiji Period.

The Meiji Restoration (called this because power was restored to the Emperor Meiji) began the colonization of Japan by the west. It is noted that during this period, the Japanese, “like other subjugated Asian nations…were forced to sign unequal treaties with Western powers. These treaties granted the Westerners one-sided economical and legal advantages in Japan.”[6] Beyond this, significant modernization and Westernization occurred. Compulsory education, now reformed to resemble French and later German systems was implemented, as well as a European-style constitution in 1889.

After being closed off from the rest of the world for so long, its seemed to the Japanese that they needed to hurry and “catch up,” so they sent scholars away to different countries to attempt to get what they needed in a more condensed fashion. However, after a certain period of time, and successfully winning two wars, all of this Westernization became repugnant to the Japanese, and there was a significant rise in nationalism again.

Western forms of modernity proved to be like a virus- once they entered the Japanese system they stayed. The symptoms were treatable, but the virus would always be there. On the other hand, the more this virus showed itself, the more nationalistic the country got. The West continued to colonize Japan until the end of World War II, when Japan was physically occupied by the US, and forced to alter everything from cultural specifics (such as what they could and could not put in cinematic or literary texts) to political structures (religion and state were now entirely separated). After two hundred years of relative peace and cultural unity, it took less than half that time for the West to rope Japan in, and force it into what they saw as submission.

While the historical evidence does show the “conquer” of Japan, and its subsequent punishment and demonization within much of Western culture (especially the US), what occurred within the cultural borders of Japan was something very different. With the sudden influx (initially desired, consequently abhorred) of so many different cultures after the Tokugawa period, it is difficult to conceive of Japanese culture not having been influenced in some way. However, the consolidation of nationalistic identity was so strong before the ports opened that even the influences that had become present were now filtered through a Japanese lens.

The three phases that Frantz Fanon discusses in the progression towards cultural decolonization are defined by Teshome Gabriel as

(a) The unqualified assimilation phase where the inspiration comes from without and hence results in an uncritical imitation of the colonialist culture; (b) the return to the source or the remembrance phase, a stage which marks the nostalgic lapse to childhood, to the heroic past, where legends and folklore abound; and (c) the fighting or combative phase, a stage that signifies maturation and where emancipatory self-determinism becomes an act of violence.[7]

If you follow Japanese history from the end of the Tokugawa Period forward, it seems that Fanon’s text is accurate and appropriate. Certainly the Japanese were fascinated by the outside culture that they had not experienced for over 200 years, but when that outside force sought to dominate their carefully nurtured autochthonous culture, the Japanese bristled. In fact, according to Donald Ritchie and Joseph I. Anderson, the Japanese reaction to new innovations in early cinema followed Fanon’s structure as well. In the beginning, the Japanese audiences “embraced the novelty of the moving picture with at least as much enthusiasm as other nations” but they did not, however, embrace the new cinematic methods, and neither did the directors. Now whether this was due to culturally bound aesthetic preference or not is still up for debate, but Ritchie and Anderson do note that in this aesthetic decision, the audience was “following what has become recognized as a peculiarly Japanese pattern of behavior: first the enthusiastic acceptance of a new idea, then a period of reaction against it, and finally the complete assimilation and transformation of the idea to Japanese patterns.”[8] If this is indeed the case, the Japanese have been in the process of decolonialization in the cinema for almost as long as the cinema has been around.

The cinema in Japan, though initially full of foreign product, soon began to create its own, complete with genres that celebrated nationalism and cultural history. Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino write that “real alternatives differing from those offered by the System are only possible if one of two requirements is fulfilled: making films that the System cannot assimilate and which are foreign to its needs, or making films that are directly and explicitly set out to fight the system.”[9] What if, in the presentation of these highly ethnocentric and history-centric pieces, Japan was able to do both? I maintain that Japan’s early genre cinema was not only a way of recuperating feelings of nationalism and pride in cultural identity, but also a way to fight the virus of colonialism that had already swept through the country.

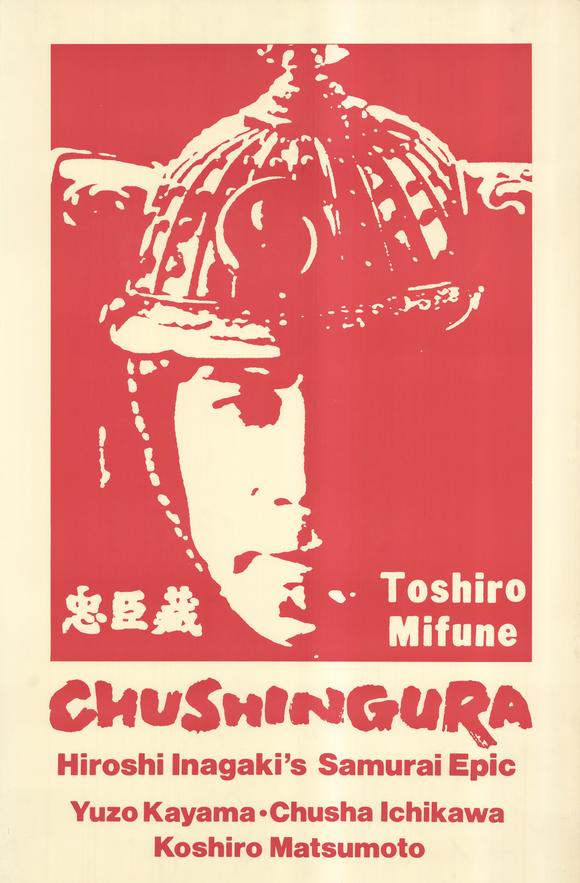

Two of the most popular genres in Japanese cinema (up until they were occupied and forced to change cinematic content) were jidai-geki (historical dramas) and gendai-geki (modern dramas). Stories such as Chushingura (the tale of the forty-seven Ako ronin), which was set in the Tokugawa period and based on historical incidents, were incredibly popular. In fact, that particular story was made into a film over eighty times between the years 1907-1962![10]

But stories like Chushingura would not have been assimilable to an outside culture, let alone the System that Solanas and Gitano mention. And the jidai-geki made up close to half of the feature films in Japan from 1910 onwards![11] The very structure of Japanese Cinema, from its origination, prohibited its cooptation and cultural dilution. By utilizing their history and cultural signifiers within the cinematic texts, they not only denied the System but also outright thumbed their nose at it.

Donald Ritchie discusses the theory that it was Japanese theater conventions that helped teleologically maintain the cultural identity of the Japanese cinema. It is a distinct possibility that theatrical features like the benshi (a live interpreter for the silent films), or the use of men acting in women’s roles did help in the cultural preservation. However, I feel that Ritchie’s own analysis is far more perceptive. He states that though these theatrical attributes might have “somehow served to preserve the ‘Japaneseness’ of this cinema, protecting it from rapacious Hollywood, [this theory] fails to take into account the fact that…any Hollywood ‘takeover’ was a highly selective and invitational affair. If anything, it was Japanese companies that took over the ways of the California studios. It is probably safe to say that Japan has never assimilated anything that it did not want to.”(italics mine)[12] While it is of utmost consequence to recognize the agency that Ritchie mentions, it is also appropriate here to mention the concept of cultural hybridity. The nature of Japanese cinema is not one of assimilation but of translation. While Japan was a colonized nation, considerably flooded with Western ideology, they managed to hybridize the west with the east, and filter it through their own cinematic language. In their own way, they did what Francisco X. Camplis was suggesting when he connected Raza cinema to Third Cinema, stating that, for decolonization, Chicano cinema needed to “explore and discover our own sense of aesthetics. Our own language.”[13]

Japan, while maintaining sovereignty over their cultural product, also enunciates their voice through the hybridization of colonial product. This technique of cultural hybridity is a highly subversive act of decolonialization, according to Robert Stam. He writes, “these aesthetics share the jujitsu trait of turning strategic weakness into tactical strength. By appropriating an existing discourse for their own ends, they deploy the force of the dominated against the dominant.”[14]Thus, when films such as Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) re-place the Western within a samurai context, it is actually creating a site of resistance.

Although Kurosawa has been called the “most Western” of all Japanese filmmakers,[15] he himself stated that he made Western films for “today’s young Japanese.”[16] While these statements might appear to have similar meaning, it is crucially significant that Kurosawa designates who his audience is. While Western critics may be able to see familiar narrative patterns or generic properties, Kurosawa’s work is a multi-layered text that, although seeming familiar to them, is still a foreign film. A.O. Scott writes that “filmed images do not require translation; we know what we see. Narratives, of course, are another story; even when they seem to be transparent, they come encrusted with local meanings, idioms and references, some of which will inevitably be lost as they move from one audience to another.”[17] Although immediately recognizable as an example of the Western genre, Yojimbo is a perfect example one of those films that, as Scott notes, is “encrusted” with its own set of culturally-bound signifiers.

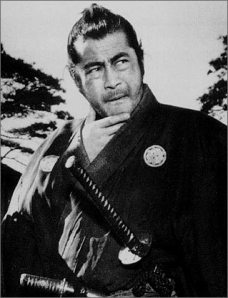

The story of Yojimbo takes place just after the end of the Tokugawa period. A ronin (masterless samurai) who was “once a dedicated warrior in the employ of Royalty, now finds himself with no master to serve other than his own will to survive…and no devices other than his wit and his sword”[18] Traveling in solitude, he comes upon a village and is fascinated to learn that it is in the middle of a turf war between two extremely morally corrupt clans. The ronin, Sanjuro, takes it upon himself to rid the town of these evil clans and their warlike ways by pitting them against each other, and letting them do the damage. In the end, the two clans do destroy each other, but the irony is that when they do, the town is left empty- a literal ghost town.

In his book, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking, Hamid Naficy writes,

Accented films embody the constructedness of identity by inscribing characters who are partial, double, or split, or who perform their identities by means of the strategies already mentioned. By so engaging in the politics and poetics of identity, they cover up or manipulate their essential incompletion, fragmentation, and instability.[19]

In Yojimbo, Sanjuro’s constant changes in affiliation between the two fighting clans underscore his fractured character. Sanjuro is a wanderer. He is a man with no allegiances and no home. He has arrived in a town that is already split in two, and now, in order to unite the town (and perhaps his own identity), he must fracture himself even further by playing both sides. To go even further, whatever side he is playing is also instable because it’s a lie. David Desser describes Kurosawa as a “dialectical” filmmaker. He describes Kurosawa’s films as cinematically split, noting that Kurosawa “offers enjoyment to the audience seeking escapism and the audience seeking substance; he speaks to the Japanese and to the West. More importantly, through a dialectical combination of the two, he speaks to both about each other.”[20] If this is indeed the case, then Sanjuro’s split identification is standing in for Kurosawa’s, a self-reflexive position that, Naficy notes, is also not unusual for accented film.

In accented cinema “neither the home-seeking journey nor the homecoming journey is fully meliorating. The wandering quests, too, are often tempered by their failure to produce self-discovery or salvation.”[21] Kurosawa’s deliberately open-ended yet dark and ironic close to Yojimbo attests to that theory. After all the effort that Sanjuro put into saving the town, the only people who are left alive at the end are the coffin-maker and the tavern keeper. Sanjuro looks at them, says, “Now it’ll be quiet in this town,” turns his back and walks away, clearly continuing on with his journey. It is clear that, although he has saved the town, there was really nothing there to save. Although nihilistic, this scenario further explores Kurosawa’s identity as an accented and hybridic filmmaker and reaffirms Sanjuro’s identity as his cinematic double. With this ending, Kurosawa clearly demonstrates his own border consciousness, which “like exilic liminality, is theoretically against binarism and duality and for a third optique, which is multiperspectival and tolerant of ambiguity, ambivalence, and chaos.”[22]

Yojimbo possessed many of the standard features of the Western genre, yet also ended up revolutionizing it. I contend that Desser’s theory of Kurosawa as a dialectical filmmaker should be widened to include his position as a dialogical filmmaker as well. Yojimbo did not remain contained within Japanese borders. In 1966, director Sergio Leone remade it in Almeria, Spain. The film starred Clint Eastwood, and was released under the title Fistful of Dollars. Jim Miller writes,

Although the storyline remained much the same in Fistful as it did in Yojimbo, a man alone playing both sides against each other, the end result of Clint Eastwood’s role brought about a whole new look at the Western hero as a lone wolf, anti-hero that was totally different from characters John Wayne had played. The anti-hero had been done before and been well received…but…[this] was a Western anti-hero who had not been viewed by American moviegoers, and that made the character and the actor who played him a different kind of Western hero.[23]

While Fistful of Dollars became the first in what would be a series of films starring Clint Eastwood as Sanjuro’s American surrogate, the Man With No Name, it is integral to recognize that the American translation of Kurosawa’s work introduced a new archetype.  My position is that Japanese films (even Yojimbo, which David Desser admits is “dependent on Western [genre] structures”[24]) subvert Western colonial narrative structures through their cultural filtration system. This is further proven by Miller’s discussion of the reception of Clint Eastwood’s character.

My position is that Japanese films (even Yojimbo, which David Desser admits is “dependent on Western [genre] structures”[24]) subvert Western colonial narrative structures through their cultural filtration system. This is further proven by Miller’s discussion of the reception of Clint Eastwood’s character.

The three central roles in the Western genre are “the townspeople or agents of civilization, the savages or outlaws who threaten this first group, and the heroes who are above all ‘men in the middle,’ that is, they possess many qualities and skills of the savages, but are fundamentally committed to the townspeople.”[25] Kurosawa’s conflation of archetypes is vital and entirely intentional. By creating a climate in which the townspeople are the savages and the hero is committed to the destruction of the townspeople, he is forcing the spectator to reflect on “a world of uncertainty.”[26] In many ways, this film can be seen as analogous to the confusion brought on by Westernization. The main villain, Unosuke (the son of one of the clans), is in possession of a gun, and waves it around like a cowboy. The rest of the men are armed only with swords. The presence of this weapon, and Unosuke’s ultimate defeat, signifies that even though the Western world might have invaded Japan historically, forcing change and cultural infiltration, the basic structures of Japanese identity are strong enough to withstand that change. Essentially, Sanjuro’s abrupt but confident departure from the town signifies the triumph of the samurai, symbol of loyalty and honor, and Japanese history, over the attempt by the West to conquer the East.

In the introduction to Donald Ritchie’s book on Japanese cinema, he traces the hypothetical life of a 50-year-old man in each period of early Japanese cinematic history. From the man in 1896, who “would have been born into a feudal world where the shogun, daimyo, and samurai ruled” to the man who “would have witnessed the forced adoption of the Gregorian calendar, the emergence of a nationwide public school system, the inauguration of telephone services…and the construction of railways,” Ritchie briefly looks at what a Japanese man might have experienced. But, Ritchie says, “through it all, he…would have been told to somehow hold on to his Japaneseness. [A] slogan indicated the way: ‘Japanese Spirit and Western Culture’ (Wakon Yosai)- in that order…[and] In this manner, it was hoped, Japan might avail itself of the ways of the modern West and, at the same time, retain its ‘national entity.’”[27] Teshome Gabriel says that Third Cinema “must above all be recognized as a cinema of subversion.”[28] By working through the ideas of Wakon Yosai, the Japanese cinema is a proud and active part of Third Cinema. Through the jujitsu model of hybridity and a refusal to dilute their national identity, Japanese cinema has, and is continuing to have, the best of worlds. They truly have subverted the dominant paradigm and are only richer as a result.

[1] Gabriel, Teshome. Third Cinema in the Third World: The Aesthetics of Liberation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Research Press, 1982.

[2] Gabriel, ibid.

[3] Gabriel, ibid.

[4]Heinrich, Amy Vladeck. Ask Asia, a K-12 Resource of the Asia Society, History of Japan, 1994. available at http://www.askasia.org/image/maps/timejape.html, Internet; accessed 16 March 2011.

[5] Michael Cooper, interviewed in “Japan: Memoirs of a Secret Empire.” Empires, narr. Richard Chamberlain, PBS, 26 May. 2004.

[6] Meiji Period (1868-1912), Periods of Japanese History, Japan Guide, 2 June 1996. available at http://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2130.html, Internet; accessed 20 November, 2004.

[7] Gabriel, ibid.

[8] Anderson, Joseph I. and Donald Ritchie. The Japanese Film: Art and Industry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

[9] Solanas, Fernando and Octavio Getino. “Towards a Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences for the Development of a Cinema of Liberation in the Third World.”

[10] Barrett, Gregory. Archetypes in Japanese Film: The Sociopolitical and Religious Significance of the Principal Heroes and Heroines. Cranbury: Associated University Presses, Inc, 1989.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ritchie, Donald. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2001.

[13] Camplis, Francisco X. “Towards the Development of a Raza Cinema (1975)”. Chicanos and Film: Representation and Resistance. Ed. Chon Noriega. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992.

[14] Stam, Robert. “Beyond Third Cinema: the Aesthetics of Hybridity.” Rethinking Third Cinema. Ed. Anthony Guneratne and Wimal Dissanayake. New York: Routledge, 2003.

[15] Desser, David. The Samurai Films of Akira Kurosawa. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981.

[16] Ritchie, Donald. The Films of Kurosawa. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1965.

[17] Scott, A.O. “Us & Them: What is a Foreign Movie Now?” NewYork Times Magazine, 14 November 2004, 79.

[18] Yojimbo, dir. Akira Kurosawa, perf. Toshiro Mifune, Tatsuya Nakadai, DVD, Criterion Collection, 1999.

[19] Naficy, Hamid. An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

[20] Desser, Ibid.

[21] Naficy, Ibid.

[22] Naficy, ibid.

[23] Miller, Jim. “Clint Eastwood: A Different Kind of Hero.” Shooting Stars: Heroes and Heroines of Western Film. Ed. Archie P. McDonald. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987.

[24] Desser, ibid.

[25] Kitses, Jim. “The Western: Ideology and Archetype.” Focus on the Western.Ed. Jack Nachbar. Eaglewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1974.

[26] Desser, ibid.

[27]Ritchie, Donald. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2001.

[28] Gabriel, ibid.

“Yojimbo” by Akira Kurosawa can stylistically be considered as a “study” for his “Sanjuro” made (in) a year after “Yojimbo” (with the same main character played by (the) [a] unique [actor] in the history of cinema (actor) Toshiro Mifune). But thematically it is quite [an] independent film that concentrates on [the] specificity of economic fight between rivaling groups of entrepreneurs with taste for semi-legal or just [outright] illegal strategies of self-enrichment (the types we [are] today in [the] 21st century [so familiar with and] know only too well). Kurosawa uses a tiny (Japanese) provincial city [in Japan] of 19th century as a setting for metaphorizing of up-to-date behavior of international cast of predatory money-makers [like our own day global corporate CEOs]. Like we [are] today (after invented wars and financial collapses [and whole host of other disasters]) Kurosawa in “Yojimbo” thinks what to do in a situation when (a) pathological greed of [the] financial decision-makers endangers the life of (human) population[s]. Again, [as] (like) we [are] today, Kurosawa was disappointed [with the] (in) traditional idea of “revolutionary transformation” of a corrupt society – the experiencee of Soviet Union and Eastern Europe is enough to discourage us from this way. Instead, Kurosawa offers in his too films Sanjuro as, in essence, a role model for our hope. Instead of “revolution” as a strategy for social-psychological transformation of life Kurosawa offers “non-participation”. Sanjuro is [an] outsider by moral reasons. It is this status (under-status[ed]) “of not belonging” [that] colors his personality as [a] moral alternative to those who while being horrified by the cruelty of the system are doomed to participate in its everyday rituals because they share many of its conventions and prejudices. The intensity of “Yojimbo’s” critical energies joins the elaborateness of its analysis of today’s formal democracy’s vices and sins hidden under the beautiful [Universalist declaration of enlightenment and] make-up[s] of its proudly humane ideological pronouncements. “Yojimbo” is full of wit and humor, but also of human emotions, suffering and joy, and real problems.

Victor Enyutin

Your blog, “Eastern Ways in Western Dress: Cultural Hybridity and Subversion in Yojimbo � Sinamatic Salve-ation” ended up being very well worth writing a comment on!

Simply just desired to say u did a wonderful work. Thanks a lot

,Dorothy

Thank you so much ! I really appreciate the feedback!

Hurrah! In the end I got a webpage from where I can genuinely obtain helpful data concerning my study

and knowledge.